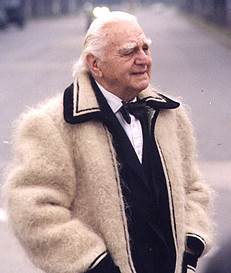

Indrei Ratiu: For the 97th Anniversary of Ion Ratiu (June 6, 1917) and the 10th Anniversary of the Ratiu Democracy Centre (July 17, 2004)

“I WILL FIGHT TO THE LAST DROP OF MY BLOOD FOR YOUR RIGHT TO DISAGREE WITH ME…”. ION RATIU’s CALL FOR PERSONAL MORALITY AND FAITH AS FOUNDATIONS OF DEMOCRACY.

“I WILL FIGHT TO THE LAST DROP OF MY BLOOD FOR YOUR RIGHT TO DISAGREE WITH ME…”. ION RATIU’s CALL FOR PERSONAL MORALITY AND FAITH AS FOUNDATIONS OF DEMOCRACY.

I have often wondered what exactly Ion Ratiu, my father, meant by those striking words he first expressed on Romanian television in 1990 during a peak-hour television debate between the principal presidential candidates, Ion Iliescu, Radu Campeanu and himself. My own understanding of what he meant that historic night has changed over the years. This short paper reflects my own most recent understanding. May it also serve as an invitation to you to share your own thoughts. What do Ion Ratiu’s now famous words mean to YOU…. ?!

During the run-up to the 1990 presidential election, the two opposition candidates (my father Ion Ratiu for the National Peasant Party and Radu Campeanu for the Liberals) suffered considerable harassment and humiliation by members of Ion Iliescu’s ruling National Liberation Front. The first post-communist era presidential campaign in Romania was drawing to a close. Although technically free and fair, it was inevitably flawed. The Ceausescu era was clearly over, but it was by no means clear whether the country’s future lay with the East or with the West, with thuggery or with civility, with communism of some kind, or with democracy.

As wealthy, seasoned political figures returning from political exile to serve their country, my father and Campeanu heard insulting slogans like “Nu ne vindeti tara!” (“Don’t sell the country!”) on the streets of Bucharest and around the country. The hours allotted to them for campaign broadcasting on state television were derisory. The opposition leaders were clearly at a tactical disadvantage. How, I suspect my father thought, under these difficult circumstances, can I achieve maximum impact, if not for this election, then at least for the future of democracy in our country?

The words he chose to use that night: “Until I become willing to fight to the last drop of my blood for your right to disagree with me I have not understood the essence of democracy” are reminiscent of a famous phrase attributed to the 18th century sceptical French philosopher Voltaire, whom my father much admired:

“Je ne suis pas d’accord avec ce que vous dites, mais je me battrai pour que vous ayez le droit de le dire” (“I disagree with what you are saying but I will fight for your right to say it”.

But my father’s phrase is FAR stronger than Voltaire’s. His addition of those words “to the last drop of my blood”…makes Voltaire’s phrase sound mild, even reasonable in comparison.

In contrast with Voltaire’s reasonable phrase, my father’s phrase is extreme. He is saying that he is willing not only to fight, but even to sacrifice his own life for your and my right to disagree with him. He then goes even further, concluding with the words: “only when we become willing to make that ultimate sacrifice, do we begin to grasp the essence of democracy….”

Why did he say this ? To shock and hopefully catch viewers’ attention within the few minutes of television prime time allotted to him? Certainly. This was, after all, the eve of a general election, potentially a turning point in Romanian history…. But today I believe his words were also about something even more important. He was deliberately challenging the legacy of Romanian communism and its official credo – atheism. He was inviting us all to dare to live differently, to become willing to actually die for a moral principle – something that most communists would have said , “only a fool would do”.

Although my father was familiar with both death and physical assault, I now believe it is unlikely that he used such strong words merely for the sake of hyperbole – a rhetorical trick to attract the attention of his audience. He had faced death as a young soldier attending military academy in Craiova, when he sustained a major head injury skiing in the Carpathians. The accident scarred him for life. Ten years later he faced death again from tuberculosis in a Davos sanatorium. And again in 1990, when his house on Str Arminendului, Bucharest was broken into by armed “miners” he is reliably reported to have challenged the intruders with the words: “Go ahead, kill me…”

So if, by 1990, my father was himself no longer afraid of either death or dying, what did he mean by deliberately choosing to turn Voltaire’s reasonable statement into an extreme call to his fellow Romanians, to become willing ourselves to actually die for the sake of democracy, in order that we might fully grasp its significance ?

To understand this, I am reminded of another powerful phrase, this time attributed to the American Founding Father Alexander Hamilton: “If a man does not stand for something, he will fall for anything…!”

Although I do not recall my father ever actually saying these words, Hamilton’s phrase is SO close to his own beliefs that I can almost hear him saying them! He is saying in effect (but the words here are mine) “if I lack a moral compass of my own to direct my path in life; if I do not believe in something more uplifting than the satisfaction of my own selfish ambitions and needs, then I, like Pinocchio in the famous children’s story, will likely fall for every passing temptation or fear, and be of no use to anyone”.

“If I do not have a guiding principal that I am willing to die for, then I am all too likely to be tempted by some passing opportunity to get rich quick, some glittering occasion to gain some material or social advantage…. or by some paranoid fear, such as the widespread fear heard on the streets of Bucharest in 1990, a fear of “wealthy former exiles out to sell the country”.

“Of work of any real or lasting value I will consequently accomplish little. And on the contemporary Romanian political scene, with its long tradition of corruption and opportunism, without a guiding principle that I am willing to die for, I, and indeed most ordinary human beings, will in due course find himself or herself utterly corrupted….”

As a Romanian patriot with a lifetime of experience of national as well as foreign politics both at home and abroad amid the Romanian diaspora, my father knew all about such temptations. He was also well aware of his own weaknesses. With his now famous words about being willing to die for another’s right to disagree with him, I believe he was not only saying something essential about himself as a political candidate, but also something about human nature, something about all of us. He was deliberately identifying with all his fellow Romanians – in our difficulties, in our struggle to live and to find meaning in our lives. But he carefully resisted the temptation to get in any way “preachy” or religious. That was never his style. And under the circumstances, such a message would almost certainly have backfired.

Although raised in the Romanian Uniate Church (the Romanian catholic church united with Rome) of his ancestors, where he served as altar-boy in his family parish church of Turda Veche (where his cousin Fr Coriolan Sabau served for many years as parish priest and later a prisoner in communist jails for his faith), as an adult, my father was not a regular churchgoer. He limited his visits to major feast days such as Christmas and Easter, which he attended every year with my brother Nicolae and myself.

He was not an openly religious man. But I remember him as comfortable with worshippers of many persuasions: Uniate, Roman Catholic, Protestant, Jewish….yet always careful to avoid fundamentalism of any kind. I and others do however recall him privately, and disconcertingly admitting, on a number of occasions, “I am a sinner”. But he always resolutely refused to discuss matters of faith, whether his own or anyone else’s.

My father’s behaviour in matters of faith suggests that he was convinced that God, whatever else he considered Him to be, is certainly the “Supreme Gentleman”, always respectful of our own free will, ever preferring anonymity for Himself – rather than having us shout about Him from the rooftops, thereby causing religious controversy and strife. Faith, my father believed, should always remain private. He owed this position at least partially, I believe, to the fact that he was raised in Turda, a community well-known for its spirit of religious toleration ever since the historic and uniquely tolerant Edict of Turda was signed there by a ruling Transylvanian Prince, in 1568.

Today I believe that my father, while giving nothing away about his own faith that night on television in 1990, also chose to add those extreme words about willingness to die for democracy, in order to appeal deliberately to Romania’s many Christian believers. I myself was not an active Christian at that time, so his appeal was lost on me personally, as well on sceptics or agnostics generally.

My father’s Christian reference that night was necessarily so discreet, it simply passed over our heads. But for hundreds of thousands of practising Christians watching the televised debate that night, his reference to the Saviour would have been self-evident, as it is for me also, today. Who, more than any figure in history, do Christians think of when they hear the words “To be willing to die for another”? Surely, Jesus Christ alone…!

To summarize, I now believe that my father’s historic words that night in 1990 on Romanian national television were designed partly to shock and provoke people into thinking, with his use of an intrinsically memorable phrase, but mainly, as a loyal national peasant (Taranist), to address himself to the important constituency of active, believing Romanian Christians of all denominations watching television that night…

His implicit message went something like this (and again the words are my own not his): “Unlike the political leaders and demagogues you have known under communism, including those here present tonight, I cannot and will not present myself as a paragon of virtue. But instead I offer you a moral code, a compass that I have personally chosen to live by, and that I invite all freedom-loving Romanians watching this debate to live by also. That code or compass is encapsulated in a willingness to die for another’s right to disagree with us… Because, after 40 years of communism, only by attempting, no matter how imperfectly, to live by such a demanding moral code, can we ever expect to make democracy work”.

Did my father get his message across successfully that night? Not in time to win the 1990 presidential election! But as the years go by since that historic presidential election, it is becoming increasingly apparent to many that his message was essential, and potentially life-changing, both for ourselves as individuals, and for the country that we love, asa whole.

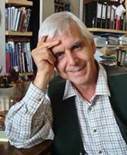

Indrei Ratiu

Bournemouth

June 2014